What Top 10% Actually Means (For a Lawyer Who Codes)

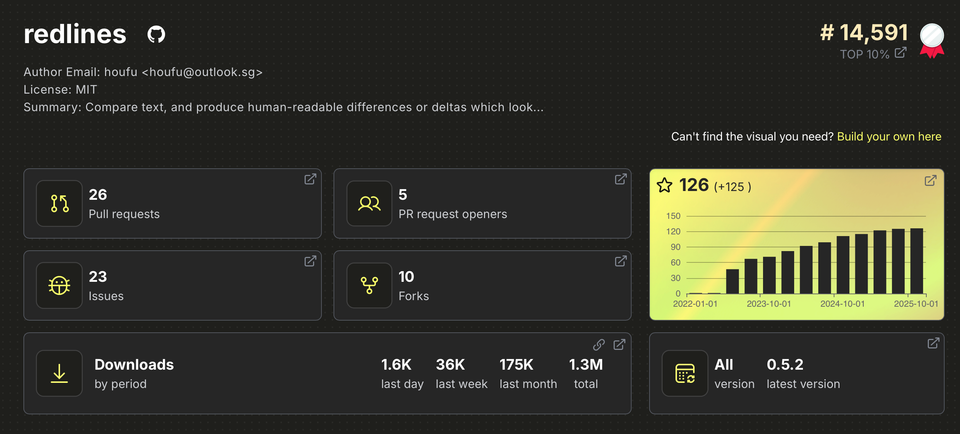

175,000 monthly downloads. Top 10% of 700,000 PyPI packages. Still a weekend project.

Two years ago, I wrote about the unexpected joys of open source when redlines went briefly viral. Last month, I discussed adapting it for AI agents. But I haven't talked about what "success" actually looks like from the maintainer's side.

Here's what top 10% means—and doesn't mean.

What Top 10% Actually Means

Being in the top 10% of PyPI packages sounds impressive. Out of nearly 700,000 packages, redlines performs better than 630,000+ others in terms of downloads and usage.

But here's what that ranking doesn't tell you:

No revenue. Enterprise companies use redlines and contribute $0. That's fine for open source—but it surprises people who think "popular" equals "profitable."

No team. I'm the only maintainer. Seven contributors have submitted pull requests over three years, which I'm grateful for, but day-to-day maintenance is solo work done on free time.

No roadmap. There's no 6-month product plan or quarterly OKRs. Features get built when someone needs them badly enough to contribute a PR—or when I need them for my own work.

According to Tidelift's 2024 State of the Open Source Maintainer survey, 60% of maintainers are unpaid, and nearly 60% have quit or considered quitting their projects. Top 10% doesn't exempt you from those statistics.

Three Hard-Earned Lessons

Defining tight scope sounds simple in theory. But what should that scope actually include? Here's what three years of maintenance taught me.

Lesson 1: Scope is Your Most Important Feature

Redlines does ONE thing: compare two text strings and show the differences. Like track changes in Word, but in Python.

That narrow scope isn't a limitation—it's the reason the project still exists.

I've been tempted by features that seem obvious. I even opened issues for PDF, HTML, and Word document handling myself. They remain open because I haven't found a way to implement them that preserves redlines' core reliability—and that's the discipline narrow scope requires.

Learning to say "no" professionally is harder than building features. As one maintainer put it: "Every line of code is a long-term liability." Every "yes" today means maintenance forever.

Here's how I respond these days: You're welcome to build it yourself—it's open source! But it's not my focus.

Lesson 2: Boring Problems Often Have Bigger Audiences Than Exciting Ones

Nobody calls text comparison "exciting." There are no TechCrunch articles about "revolutionary new way to show changes just like Microsoft Word"

But hundreds of people need it. They're solving problems like:

- Comparing contract drafts without uploading to third-party services

- Tracking legislative changes (PLUS Explorer uses redlines for this)

- Building AI tools that need to show what changed

- Working in Jupyter notebooks without Word

The gap between enterprise legal tech ($50K/year platforms) and solo practitioners ($0 budgets) is enormous. That gap needs filling.

The issue of citing hallucinated cases is a stark reminder of the gap solo practitioners face.

Lesson 3: Validation Comes from Utility, Not Credentials

I rarely check redlines' download stats. When I discovered it was top 10%, my first reaction wasn't pride—it was surprise. "Is this even real?"

144 GitHub stars feels modest. I've seen projects get thousands in weeks. I'm a lawyer who codes, not a software engineer. When I presented redlines at GeekCamp Singapore, people asked, "Wait, you're a lawyer?"

That surprise stuck with me. So did the question: do these numbers actually mean I belong?

Here's what I learned: I was looking for validation in the wrong places.

What doesn't sustain you:

- GitHub stars (comparing yourself to "real" projects)

- Recognition from developers (proving you belong)

- Download metrics (abstract numbers that feel unreal)

- Top 10% rankings (impressive but hollow)

What does sustain you:

- Solving your own problem first

- Discovering unexpected use cases you never imagined

- Seeing people accomplish things they couldn't do before

- Utility over validation

I built redlines for my own legal legislation comparison work. Then people learning AI started using it to track how LLMs rewrote their prompts. That use case never occurred to me.

That's what kept me going. Not stars. Not payment. Not even recognition from the developer community.

People were solving real problems with something I built. The problems were different from mine. The users had different backgrounds. None of those differences mattered. The solution worked.

Your impostor syndrome wants you to seek validation from credentials, metrics, and community acceptance. That's the wrong game. You're not building to prove you're a "real developer."

You're building to address real needs. When it works, validation comes from utility—someone, somewhere, using your code to accomplish something they couldn't do before.

For lawyers who code: your background isn't a deficit requiring proof. It's why you see problems others miss. Build for those problems. The right users will find you.

Top 10% didn't make me feel like I belonged. Watching AI learners solve problems I never anticipated—that did.

The Honest Call to Action for Lawyers who Code

Don't start with a roadmap or a GitHub repo. Start smaller:

What problem are you solving manually right now? What do you copy-paste three times a week? Build something that saves you 15 minutes. Make it work for you first.

Then share it with one person. A colleague. A friend in another firm. Someone in a legal tech Slack. Not to prove you can code—just to see if it helps them too.

That's how 175,000 monthly downloads happened. Not from a grand plan. From tackling my own boring problem, sharing it once, and being surprised by who it helped.

You don't need to become an open source maintainer. You don't need top 10%. Just solve your problem, show someone, and see what happens.

Start there.

Member discussion