I Build Infrastructure. Jamie Vibe Codes Tools. Here's What I'm Missing.

I compared my GitHub to Jamie Tso's and felt unproductive.

My profile: 70 repositories, redlines library with 148 stars and 177,000 monthly downloads on PyPI, top 10% quality ranking. Years of work.

His profile: 4 tools built in 2-3 months using "vibe coding"—LLMs generating TypeScript code from natural language descriptions.

The velocity gap was stark. RedlineNow, his instant redline tool: 5 commits over 2 days in December 2025. Done. Shipped. Thirty stars and 11 forks.

My redlines library: hundreds of commits over 3 years.

30-90x velocity difference.

My first reaction: What am I doing wrong?

Then I read my own blog post about the redlines library:

Every line of code is a long-term liability. Every 'yes' today means maintenance forever... Scope is your most important feature. I've been tempted by features that seem obvious. They remain open because I haven't found a way to implement them that preserves redlines' core reliability.

I realized: This isn't a productivity problem. It's a question of what we're building for—and how long it needs to last.

I build infrastructure. Jamie builds tools. Neither is wrong. But applying the wrong mindset to the wrong problem kills velocity.

Two Mindsets

There are two fundamentally different ways to approach building legal tech. Most lawyers unconsciously default to the wrong one.

The Tool Mindset

Jamie's approach optimizes for immediate utility.

Take RedlineNow:

- First commit: December 6, 2025

- Latest commit: December 7, 2025

- Total commits: 5

- No tests, no CI/CD, no edge case handling

- Ships when it redlines contracts for his Clifford Chance team

Done in 2 days. Thirty stars. Eleven forks. It works.

Or SignaturePacketIDE—automated signature packet generation for M&A deals. Five commits total. Twenty stars, fourteen forks. The most-forked project, proving real usage in BigLaw deal teams.

Jamie's philosophy, from interviews:

Pick one painful workflow, prototype fast, ship to 3-5 power users, iterate weekly... Decide build vs buy with a checklist, not by defaulting to either path.

He asks: "Does a vendor tool exist for this niche workflow? No? Can I build it in a weekend? Yes? Ship it."

In an interview with Artificial Lawyer, Jamie explained his build-vs-buy decision framework.

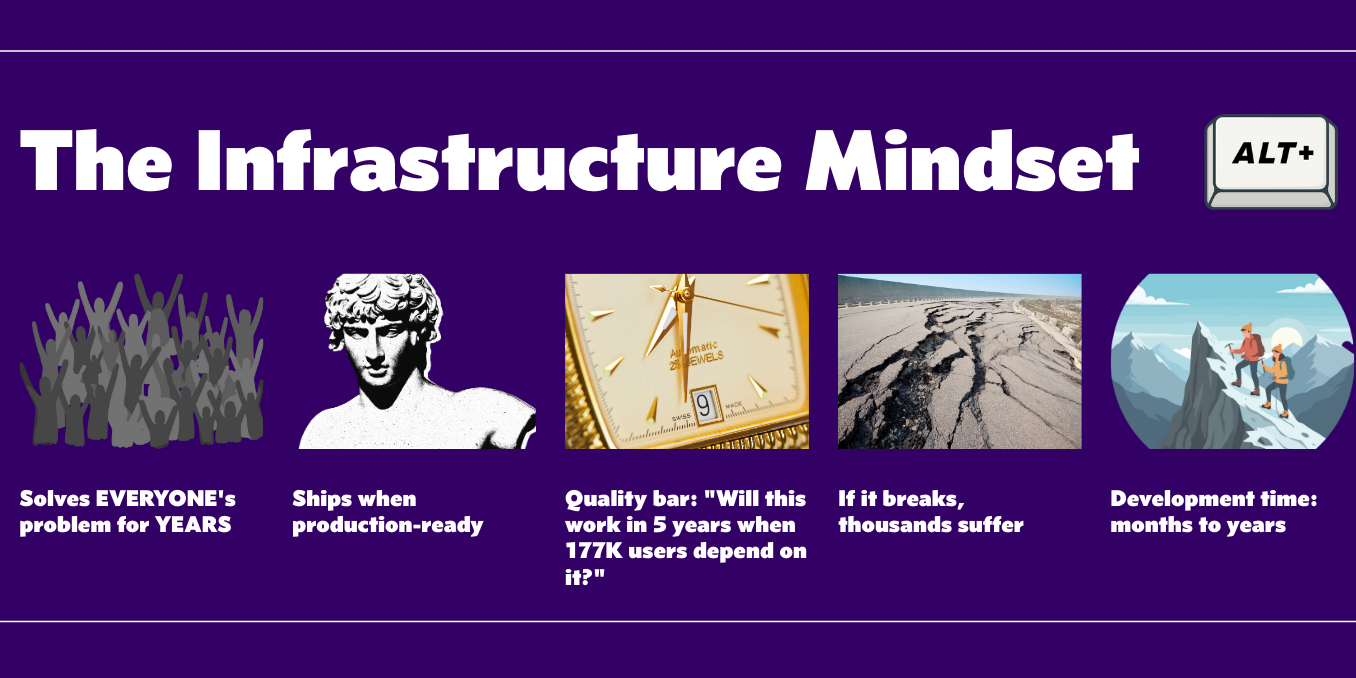

The Infrastructure Mindset

My approach builds a framework that focuses on the long term.

The redlines library:

- Hundreds of commits over 3 years

- Comprehensive test suite

- API documentation hosted at houfu.github.io/redlines

- Published on PyPI with semantic versioning

- 177,000 monthly downloads

- Top 10% quality ranking

I wrote about this (What Top 10% Actually Means):

Scope is your most important feature... I've been tempted by features that seem obvious. I even opened issues for PDF, HTML, and Word document handling myself. They remain open because I haven't found a way to implement them that preserves redlines' core reliability—and that's the discipline narrow scope requires.

(NB: Last week, redlines finally reads basic PDF documents.)

What Makes Jamie's Vibe Coding Work

Jamie ships dramatically faster because he's optimized for a different goal.

Look at his repository patterns:

- RedlineNow: 5 commits in 2 days, no tests, ships when it works, 30 stars

- SignaturePacketIDE: 5 commits, similar velocity, 20 stars and 14 forks

- Tabular_Review: 8 commits over 6 days, has Docker but no tests, 14 stars

All of Jamie's projects are open source on https://github.com/jamietso—free to fork, study, and adapt for your own needs.

The pattern: Ship when it works. No iterative refinement. Tools appear "done" after initial commits.

Why is it fast? Infrastructure is not a key concern. When building RedlineNow, Jamie doesn't ask:

- ❌ "What if users have different file formats?"

- ❌ "What if this needs to scale to 1,000 users?"

- ❌ "Should I write unit tests?"

He asks:

- ✅ "Does it redline the contracts my team reviews?"

- ✅ "Can I ship by Friday?"

- ✅ "Do 5 colleagues find it useful?"

Jamie doesn't carry infrastructure weight. His tools serve his Clifford Chance team. If they break, he fixes them for that team. No one else critically depends on them.

The fourteen forks on SignaturePacketIDE suggest others find value. But if Jamie stops maintaining it tomorrow, those teams can fork and maintain their own versions. No 177K users depending on daily reliability.

What I'm Missing

Legal training hammers certain habits into us:

- Precedent and reliability: Every decision must withstand scrutiny

- Edge cases and risk management: "What if someone sues?"

- Professional responsibility: Your work affects real people

- Defensibility over speed: Better sure than wrong

These instincts serve us well in legal practice. They kill velocity in tool building.

Real example: I wanted to build a contract review helper for my work.

What I did (infrastructure thinking):

First, I researched similar tools. Found docassemble which can be used for multiple contract types. Investigated security compliance. Worked out network requirements. Thoroughly test cases until I was sure it was safe.

Three months later: A small launch. Only starts to gain traction after repeated mentions during training, emails and other channels. Repeatedly remind everyone that Legal is still around, and legal is still checking.

What I should have done (tool thinking):

- Weekend 1: Vibe code a script that reviews the 3 contract types I actually see weekly

- Weekend 2: Test with my work, refine the prompts

- Weekend 3: Share with 2 colleagues, incorporate feedback

Total: 3 weeks to working tool.

If requirements change next year? Rebuild it in another weekend. Cost: 6 days of effort total. Benefit: 52 weeks of productivity.

The Maintenance Reality I've Learned

Here's what examining Jamie's code revealed about disposable tools.

My contract generator uses Docker and stable software choices. Even with best practices, maintenance isn't zero—it's a few hours per year at minimum. That's sustainable. I've designed it so the next person can maintain it. That's manageable.

When I examined RedlineNow, Jamie's instant redline tool, it uses diff-match-patch—a library Google archived years ago. When dependencies break—and they will—these tools will stop working. Jamie will rebuild or abandon them. That's fine for internal BigLaw tools built for immediate needs.

But for open source contributions serving the community? Or if you would like others to build on or use your project? Sustainability matters.

My redlines library takes months to build because I choose maintained dependencies and regularly check that they still work through Python version and package changes (such as from poetry to uv). I take advantage of Hacktoberfest to check on the library and invite others to contribute it (which isn't as easy as just making it available). I say no to features because every yes is a long-term liability.

That's not infrastructure thinking slowing me down. That's the cost of building things that last—things 177,000 monthly users can depend on.

Jamie's approach works for disposable internal tools. Mine works for sustainable open source. Neither is wrong, but if you would like to make software that lasts, there are more considerations.

When Vibe Coding Breaks - And It Will

The "future you" problem: You vibe code a weekend tool using LLM-generated code you barely understood when it worked. It runs great for a few months. Then it breaks - Python updated, some dependency failed, or an edge case you never tested appeared.

Now you need to fix it. But you can't figure out how it works anymore. The LLM wrote clever code that handles cases you didn't think about in ways you don't fully grasp. Rebuilding from scratch might be faster than debugging.

This is where infrastructure and tools diverge: With infrastructure thinking, you understood the code, chose maintained dependencies, and can fix it. With vibe coding, the code is opaque and dependencies might be abandoned.

It's not "if" but "when" something breaks. Jamie can rebuild quickly or lean on Clifford Chance's IT support. Solo counsels? You're debugging at 9pm when a deal closes tomorrow and the tool that worked for months suddenly doesn't. It's downright embarrassing when a fancy tool you made yourself fails in front of your clients or bosses.

Prevention: Keep tools truly disposable. Document the manual backup process before you build the automated one.

Decision Framework

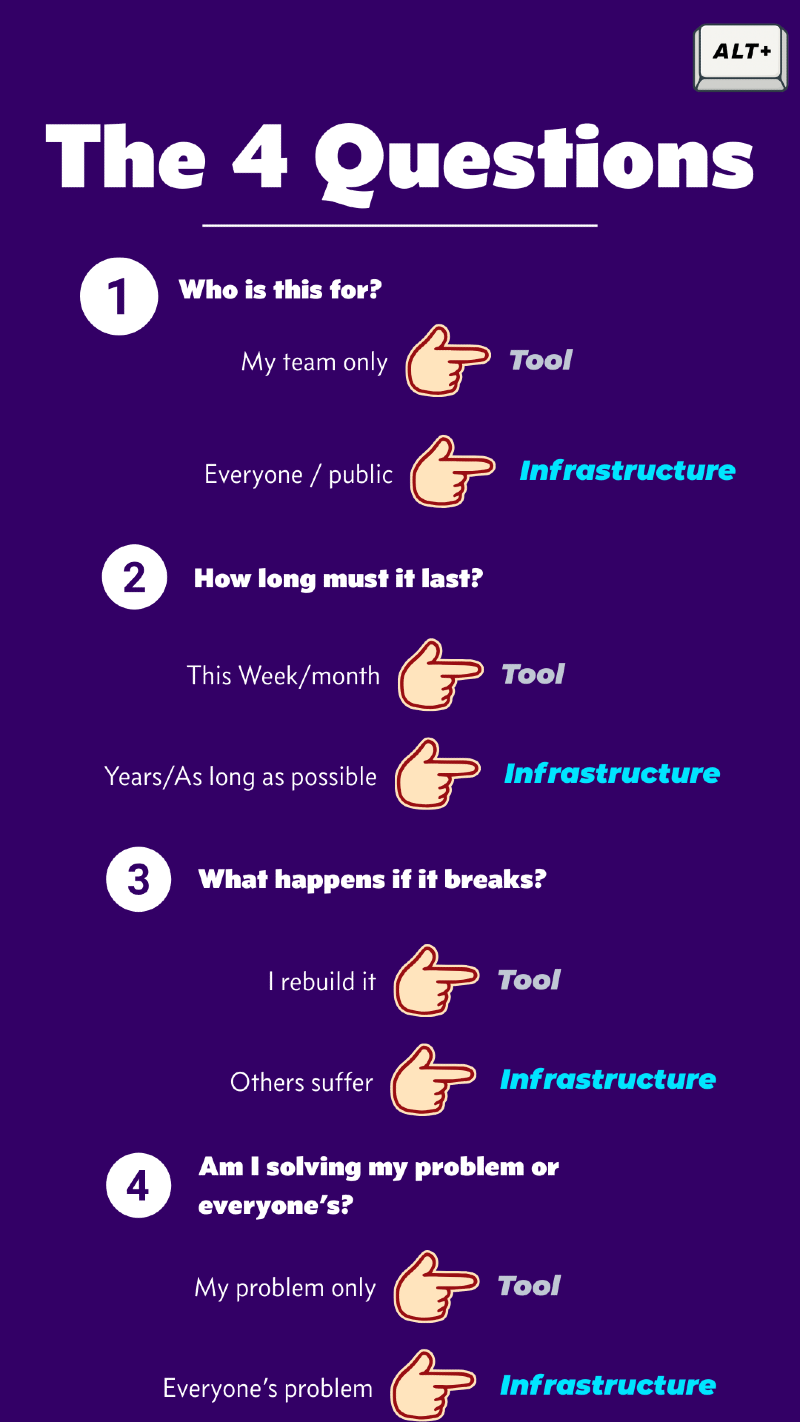

Before starting your next project, ask 4 questions. Your answers determine everything else.

What To Do With Your Answers

If answers are: my team, this week, rebuild, my problem → Build a TOOL with vibe coding

Approach:

- Ship when 5 users say it works

- No tests, minimal infrastructure

- Rebuild if it breaks

- Velocity: days to weeks

- Use Gemini (like Jamie) or your favourite LLM with a IDE you are comfortable with

If answers are: everyone, years, others suffer, everyone's problem → Build INFRASTRUCTURE with traditional programming

Approach:

- Proper engineering (tests, docs, API design)

- Handle edge cases thoughtfully

- Long-term maintenance plan

- Quality bar: production-ready

- Velocity: months (worth it for infrastructure)

The Mindset Shift

Old approach: Default to infrastructure thinking for everything

New approach: Consciously choose tool vs infrastructure mindset BEFORE starting

Jamie's advantage: He naturally uses tool thinking for tool problems. Works at Clifford Chance where infrastructure already exists—he fills gaps with disposable tools.

My challenge: Building public infrastructure for Singapore's legal community, I default to infrastructure thinking. Need to consciously switch for internal projects.

Conclusion

Jamie ships faster because he builds tools with tool thinking. I ship slower because I build infrastructure with infrastructure thinking. Neither is wrong.

The problem: I've been applying infrastructure thinking to tool problems. That kills velocity.

The solution: Ask the 4 questions. Choose your mindset consciously.

For solo counsels and small teams: You probably need MORE tools, LESS infrastructure. You shouldn't carry the weight of 177,000 monthly downloads. Build tools for your team's immediate needs. Vibe code without guilt. Ship in weekends, not months.

My goal for 2026: Keep building infrastructure where it matters—redlines serves real needs that justify the effort. I built CLI tools for Claude Code agents following this principle. But for internal tools? Switch to tool thinking. Ship in weekends, not months.

For internal tools you'll rebuild or abandon? Jamie's approach works. For open source serving the community? Infrastructure thinking is the only sustainable choice. The question isn't "should I think like Jamie" but "what am I building and for whom?"

The question that changes everything: Am I building a tool or infrastructure?

Everything else follows from that answer.

This post is open source. View the source files, discussion notes, and revision history on GitHub.

Member discussion