When Building Gets Cheap But Knowing Stays Expensive

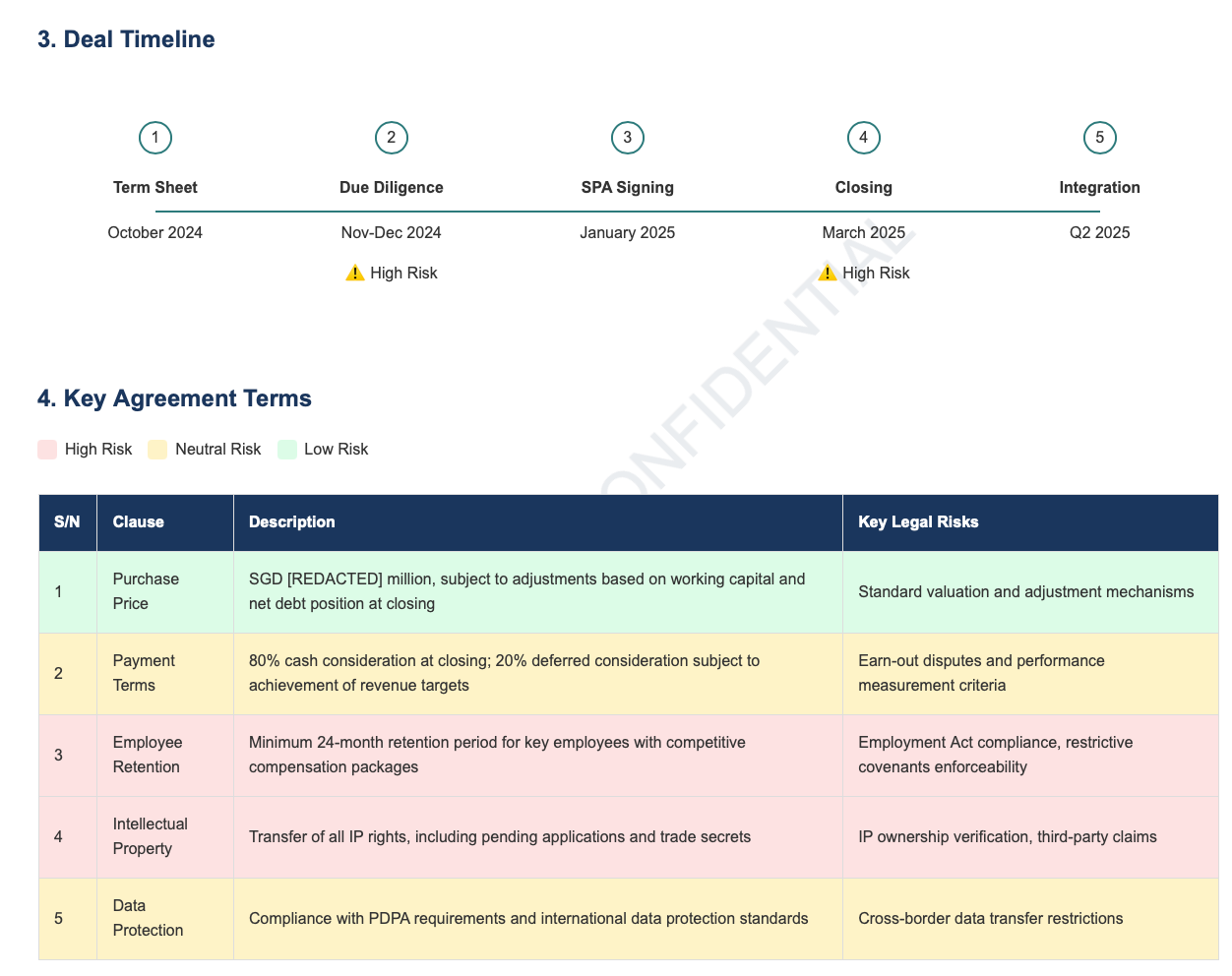

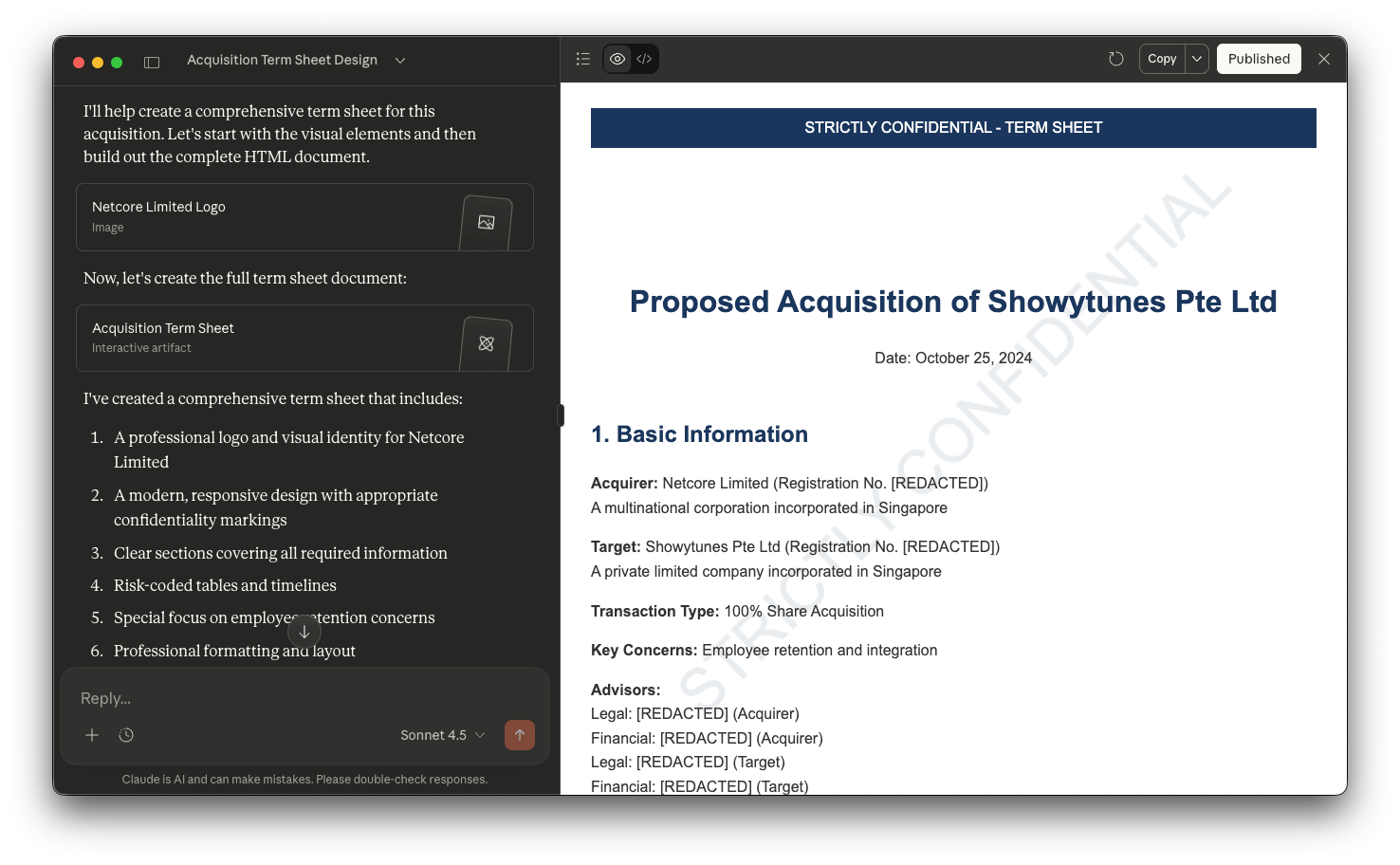

In 2024, I spent hours crafting a 3-page prompt to generate an M&A term sheet for a legal tech competition. The result was a 4-page HTML document with timeline diagrams, color-coded risk tables (red/yellow/green), and professional typography that no standard Word template could match.

It felt wasteful. All that time for a prompt that I was only going to use once.

But I also couldn't answer a simpler question: would it have actually served a client better than a standard template? I was disqualified from the competition before seeing results, so I never found out. And even if I had won, a competition judges creativity and novelty—not whether clients actually prefer this format for real legal work.

I've written before about how that prompt competition experience revealed a larger shift in legal tech, but the real lesson wasn't about prompt engineering—it was about uncertainty.

Last year, after seeing Legora and Harvey (AI-powered legal research and contract analysis tools) demo their table-based comparison features, I decided to take matters into my own hands. I created comparison tables to review competing recruitment agency contracts. Instead of reading a narrative for each contract, you can read across and get the details for all the contracts. The tables took about an hour. (I ran a review prompt to get the information for one contract in a column, then joined several to form a table) I believed a comparison table was better—visual comparison, scannability, faster decision-making.

My client's response? A polite "thanks."

I didn't press for more feedback. It was an experiment, and I didn't want to make it awkward. But here's what bothers me: I still don't know if it actually helped.

How do you justify spending an hour on custom tables when you don't know if clients prefer them over a standard email? How do you know when a new approach is worth it versus when clients just want the familiar?

When Tools Take 30 Minutes to Finish, Everything Changes

Most people would agree that AI has or would change the legal profession. But you'd be hard-pressed to find a consensus on what exactly has changed. We are still figuring out what are the full capabilities of AI, including within the legal domain.

As such, the answer is hiding between the lines of people’s experiences.

Sam Harden's "The Legal UI Revolution" describes building two client-facing tools in 15-30 minutes each using Google Gemini:

- Living Will & Health Care Proxy Interactive Tool - Instead of sending a client paper forms and a letter, he created a web app that educates clients on why they need these documents AND lets them complete the forms interactively. Time: ~15 minutes.

- Ladybird Deed vs Living Trust Visualizer - A decision tree showing clients pros/cons of each option with scenario-based recommendations. Time: ~30 minutes.

"Both of these could easily have taken 6 months and 5 figures of development cost just 4-5 years ago. But now it takes just a half hour."

What changes when creation is this cheap? From a creator's perspective, you don't need to justify the investment anymore. No budget to defend, no team to coordinate, no long-term maintenance plan required. Build a tool for one specific task, use it once, and discard it when you're done. The value isn't in reusability—it's in solving the immediate problem.

The ramifications of this change become even more significant when you realize that we are still underutilizing what AI is capable of. AI can now build interactive tools, visualizations, custom decision trees, and color-coded diagrams in minutes. Not just text, but working applications. Are you still writing a memorandum using words and paragraphs?

AI Eliminated the Wrong Constraint

The traditional barrier to custom legal tools was technical feasibility:

- "Can I afford 6 months and $50K to build this?"

- "Do I have the coding skills?"

- "Will the technology even work?"

AI removed that constraint. Now we can build anything in 30 minutes.

But the real bottleneck was never "Will this work?" (technical risk).

It was "Does this actually help clients?" (client value).

And that question remains unanswered.

AI made building cheap—but it didn't make validation cheap.

The uncertainty hasn't disappeared. It's just shifted from "can I build this?" to "should I have built this?"

My 2026 Resolution: Build and Measure

AI removed the technical barrier. Now I need to address the validation gap.

Build single-serving legal software for regular clients and matters—not just VIPs or high-stakes deals.

Custom interactive tools that might work better than templates. Contract comparison visualizers. Timeline dashboards. Decision trees for specific legal questions.

Explicitly ask clients which they prefer.

Not "was this helpful?" but "I gave you a visual table instead of a traditional memo. Did that work better for you, or would you have preferred the standard approach?"

Track what I learn.

Which clients find the new approach valuable? Which prefer the traditional template approach? When does the investment pay off?

Start with low-risk problems.

Client education tools, decision support for low-stakes choices, process management. Not authentication systems or compliance tools.

The goal isn't to prove that bespoke is always better. It's to run experiments, not declare best practices.

How to Build Your First Experimental Tool

Here's a quick tip on how to use your favorite GenAI to get started:

- Open your favorite tool. Sam Harden used Gemini (it's free! for now). I am more familiar with Claude and ChatGPT. Many leading legal tech tools also allow you to use chat, so if you plan to divulge something secretive, you can use them too.

- Start describing what you want in plain English.

- If I want a term sheet that made use of web technologies, the prompt was

Output the term sheet in the form of a HTML page. - For my color coded risk table, I started by describing the table and then the color coding.

The output of this section is a table with 4 columns: S/N, Clause, Description and key Legal Risk. Add a row for each key agreement term, and include all of them in the table. Color code the entire row based on the risks levels: Red (High Risk), Yellow (Neutral), Green (Low Risk). Add a legend to describe the color coding used. - You might not get it right the first time. (I learned this building CLI tools that AI agents actually use—AI doesn't always work the way you expect.) Think carefully about what you might be missing. If you're writing a web page, you may have to use web design language such as

Use a responsive, modern page design.The leading GenAI solution now provide a "canvas" which allows you to see your output in a side bar and specify any changes you want to the output.

- If I want a term sheet that made use of web technologies, the prompt was

Security note: I mentioned in passing what you should do if you are concerned with client confidentiality. But really, I would be focusing on “toys”. Start with low-stakes educational tools or internal process documentation before client-facing deliverables.

When experiments fail: Some tools will take longer than expected. Some clients will prefer the traditional memo. That's fine - you're learning what works for the people around you, not committing to a permanent change. If your first attempt doesn't work, try a simpler version or a different client. The point is affordable experimentation, not perfect execution.

I'm treating experimentation time as continuing education. If a tool saves time on the next similar matter, it pays for itself. In Singapore's market, where clients expect efficiency but may not understand AI, I explain the outcome (faster turnaround, better visualization) rather than the method.

The Permission We've Been Waiting For

AI didn't eliminate uncertainty—it made uncertainty affordable.

The traditional constraint was technical: "Can I build this?" That required proof before investing 6 months and 5 figures.

The new constraint is validation: "Does this help clients?" That requires experimentation.

When building costs under an hour and a few dollars in API credits, you can afford to find out through building, not prediction.

My custom tables might not have impressed my client. Or maybe they did help but clients don't think to mention it. Or maybe I'm creating "workslop"—work that looks innovative but lacks substance. The honest answer is: I don't know.

But in 2026, I'm giving myself permission to not know in advance.

I'm going to build the tools, deploy them, and explicitly ask clients what actually served them better.

Because maybe the real waste isn't spending an hour on a tool that doesn't help.

It's spending a long time wondering whether it would have.

Member discussion